Britain will publish its first budget under a new party in government in 14 years on 30th October. Ahead of it, Prime Minister Keir Starmer said his government is “going to have to be unpopular” in a high-profile interview. In areas such as planning reform, I believe Starmer is proposing wise if unpopular policies. His government’s economic strategy, however, appears to me to contain elements that are both unwise and unpopular.

Britons think the country is in a bad state, especially in areas impacted by the economy

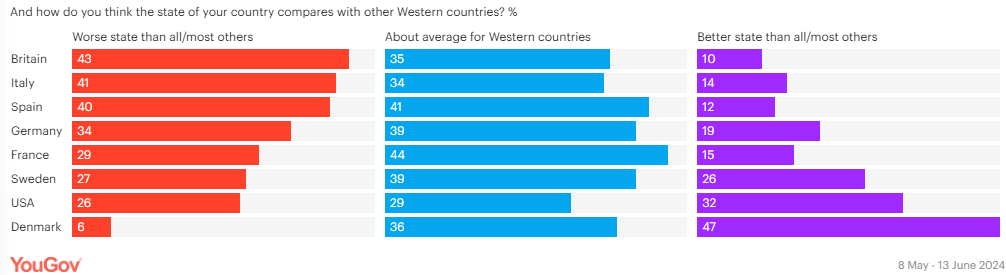

A recent YouGov survey found Britons have the worst view of the state their country is in, and are also most likely to say the countries in in a worse state than its peers:

In a separate poll, YouGov asked people which issues were most important in determining how they will vote. For comparison, I also provide data from a YouGov survey asking Americans about their top priorities.

In both countries, cost of living and the economy are top issues. But if one adds others issues in which economic policy is a key factor such as health and taxes, Britons are far more focused than Americans on economic policy broadly defined, with such issues chosen by 70% of Britons as most important to them, compared to 48% of Americans.

Britain’s economy has been hobbled by weak productivity growth

Had productivity increased under the Tories at the same rate it did under Labour, all else being equal, the economy would be 16% larger today. That would mean people were more prosperous independent of government, and deliver higher tax revenue to fund public services and benefits, or cut taxes.

Labour’s plan for productivity is a private sector investment boom - and cuts to public investment

In the long-run, productivity is a function of investment. Investment generates capital of various kinds, such as financial, physical, intellectual (technology), human (education) and social, which workers can use to be more productive.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves knows this. When she set out her economic vision at the Mais Lecture in March, she mentioned “productivity” 27 times and “investment” 35 times. The Labour manifesto for the 2024 election mentioned “investment” 59 times. This is welcome, since the OECD finds Britain’s gross investment as a percentage of GDP has been over 20% below the OECD average over the course of the last two governments.

When it comes to public investment, however, Labour is not planning raise investment - it is planning to cut it, according to estimates of Labour’s plans by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The manifesto explicitly says Labour aims to “unlock additional private sector investment” through reform (a term mentioned 49 times in the manifesto) and strategic use of public sector investment.

The logic behind Labour’s plan appears ill-founded

The motive for Labour’s plan appears to be its zeal for stability. Labour is so focused on stability that it coined the term “securonomics” to describe its economic vision, put “deliver economic stability” top of the six “first steps for change” in its manifesto, and adopted fiscal rules that are more constraining than the Conservatives’. The cuts to investment result from that framework.

To bring this to life, just before the election, Sharron Graham, head of one of Britain’s largest unions, called for “wiggle room” to enable “borrowing to invest”. In response, Bridget Phillipson, now Education Minister, said: “what we saw under the Conservatives was what comes in playing fast and loose with the public finances. And it's working people who pay the price, they're paying more on their rent and their mortgage every single month because of Liz Truss and that cavalier approach they took.”

This is a somewhat mind-boggling exchange. The Truss “mini-budget” increased government borrowing by ~1.5% of GDP, while the IFS estimates Labour’s current investment plans will lower borrowing by ~0.5% of GDP; and Truss used the borrowing almost exclusively for tax cuts, not investment. It was also managed poorly, most notably by failing to follow norms for assessing the impact of the measures with the Office for Budget Responsibility. There is simply a world of difference between a large borrowing increase to fund tax cuts and modestly increasing, or even not cutting borrowing to invest in public services offering strong investment cases.

The case for investing in Britain’s public services is strong

An independent report by Lord Darzi was just published into the largest public service, the National Health Service. One of its headline conclusions was: “productivity is too low…[a] desperate shortage of capital prevents hospitals being productive”. In education, the latest update I could find stated 119 schools “will need one or more buildings rebuilt or refurbished” due to containing Reinforced Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (RAAC), a material that was found to have been extensively used beyond its design lifespan. In defence, to cite a very different service, the Navy has two aircraft carriers which cost a combined £7.6b and can each carry 36 F-35 fighters, but the entire British military, including the Air Force, currently has only 30 such fighters in operational service.

Such situations create strong investment cases. Aircraft carriers are very expensive, but Britain already paid for those - it just needs enough planes to put on them. Likewise, it built schools and hospitals, and is paying the salaries of teachers, doctors and nurses - it just needs to provide them with safe facilities to work in and a quantity and quality of equipment that allows them to do their jobs well.

Equally importantly, public services are key enablers for the private sector investment boom Labour is targeting. Another of Lord Darzi’s conclusions is that the “NHS is not contributing to national prosperity as it could”, with 2.8m people (5% of the population) economically inactive due to sickness and millions more in work but impeded to some degree by a medical need that they are on a waiting list to receive care for. Businesses are less likely to invest in a country whose workforce is increasingly unwell. Housing is the #1 cost for most people and Labour’s manifesto has committed to a ~50% increase in home construction, much of it from the private sector - the people moving into those home will need public infrastructure, from roads to buses to schools and primary care facilities (GP surgeries, in the UK).

Increased public sector investment can be easily funded

Given public sector net investment is just 2% of GDP and Britain’s planning regime is not known for its agility, I think funding is unlikely to be a constraint on increasing public sector investment. The constraint I see is the government’s ability to execute investment effectively. Running any large program is difficult, and Britain is fresh from one of the great investment debacles in its history, amid other recent failures.

I will briefly comment on tax given the run-up to the budget is seeing extensive discussion of “taxing the rich”. I see a strong case for one type of such tax, a progressive land value tax whose creation was recommended over a decade ago by a panel chaired by a Nobel prize-winning tax economist. Beyond the sound theoretical basis for it, there are clear examples of it being levied successfully in peer countries, notably in the relatively low-tax (and highly productive) US. By contrast, an

However, I think it is imperative that people do not mistake taxing the rich for a substitute for increasing productivity. As I noted above, if productivity had grown as fast under the Tories as it had under the previous Labour government, all else being equal the economy would be 16% larger. No tax increase comes close to an effect of this magnitude. The largest tax raising proposals of the 2024 election, from the Greens, were less than half that size (6% of GDP), were in no way all on the rich (most of the revenue came from a carbon tax which would impact everyone) and were assessed by the IFS as “unlikely… [to] raise the sorts of sums they claim - and certainly not without real economic cost”, because they would “increase disincentives to work and to invest”.

Whatever the outcome on tax, if borrowing is necessary, a “catch-up” investment wave is an excellent case for doing so. The spending will not be recurrent, as it will at least in part be making good under-investment in prior decade. It should generate a direct return that lowers public spending in future, all else being equal, and also grow the economy, which improves debt sustainability, typically measures as debt or interest payments as a share of GDP.

Why is Labour so hestitant to invest and can people change its views?

This section will range beyond facts and data, but another topic I have seen widely discussed is why is Labour is acting in this questionable manner. In the more fetid corners of social media, it is attributed to corruption or mendacity. This strikes me as demagoguery. I think they feel they have no choice. Labour is subjected to such relentless attack for over-spending, that they feel they have to over-correct in the other direction, especially so soon after the Truss calamity.

If bad economic policy is borne of politics, then politics can change it. In recent weeks many MPs have recounted their constituents’ impassioned opposition to a proposal to remove winter fuel payments from all but the poorest pensioners. While admittedly nowhere near enough to stop Parliament voting for the measure, over 50 Labour MPs abstained and a handful more voted against it, and it seems unlikely the government is not learning some lessons from that reaction. The two-child limit on child tax credits is another measure the government has been hammered on and while it hasn’t changed course there either, the Guardian has discussed briefing that it is planning to do so.

It would be helpful to replicate some of that passion for public-sector investment. It’s not that an obsolete MRI machine is as bad as child poverty or a pensioner dying from cold. It’s that, over time, the former leads to the latter. Deferring important investments saves money in the short term, but in time the chickens come home to roost. To quote the Darzi Report again, the problems impeding the NHS arose in part because “the capital budget was repeatedly raided.” If MPs saw more constituent interest in issues such as inadequate maintenance, obsolete equipment or a lack of needed public transport, that may change Labour’s assessment that politics forbid assertive investment in the public sector.